CLASSEN SPARKLING

This unusual bottle has had many collectors bewildered with

precisely what it represents. They are not very numerous and the majority were

found in the ‘big dig’ of about 1998 in San

Francisco. Most have been found in blue with nearly as

many in aqua. Embossed CLASSEN & Co. SPARKLING, surrounding crossed

anchors, one doesn’t have to guess it is a product of the soda water maker,

James Milton Classen. While his story is interesting, I would like to just

focus on this one product. Classen was born in New York

and, like so many Easterners, got caught in the lure of gold in California. While establishing a successful soda water business in San Francisco, he returned to his hometown

several times.

In 1863 Classen left control of his Pacific Soda Works to

his partner, John Rohe, and returned to New

York for nearly two years. While there, he created

another somewhat complementary product for his business in San Francisco. It wasn’t

exactly the same and I am guessing he saw it as a potentially new market

product. He devised the bottles and designed labels for the product which he

copyrighted to prevent protection from possible counterfitting. On November 12,

1865, he received federal protection for his Anchor Brand sparkling cider.

.jpg)

Embossed as noted above, the bottles appear very similar to

soda water bottles of the day, with the biggest exception being a more refined

top. A big question remains about whether the bottles were designed for single

use. Was the cider a product of the East or were the bottles filled in the

West? The labels are very clear that it was a product of New

York for the California

market. This seems a little incredulous with regard to the expense involved,

especially if the bottles were for single use. Of course, he may have shipped

the bottles while empty along with barrels of cider, and bottled the product at

his soda works in San Francisco.

The answer is not clear.

This label was submitted to the U.S. District Court for the

Northern District of California as an example of his federally protected copyright.

While it is true that Classen did not avail himself of the recently adopted

trade mark law for California,

however; there was no federal trade mark protection until 1870. It was not

unusual for proprietors to use federal copyright laws for interstate protection

since California

trade marks were only enforceable within the State. Copyrights provided

interstate protection. He apparently knew the law well for Classen had already

received a trade mark in 1863 for his Pacific Soda Works bottles, which he

never planned for use beyond the State boundary.

The sparkling cider project was apparently not successful as

it was short-lived. No newspaper advertisements were located for the project

which was a kiss of death. Nineteenth-century marketing depended heavily on

reaching out to the public through papers. It is not clear when Classen became

disillusioned with the soda water business, but by 1867 he exited the Pacific

Soda Works and left it to his partner, John Rohe. Classen had already dabbled

in the real estate business by this time and he saw a much better road to

success. For the following twenty years, he became a successful ‘capitalist’,

and is even noted as a ‘stock broker' in the 1880 U.S.

census for San Francisco.

Unfortunately, he let most of his wealth slip, and by the time he died, on

September 9, 1891, he had little left. His wife was forced to take up residence

in the “Old People’s Home of San Francisco”, where she slipped into oblivion in

1905.

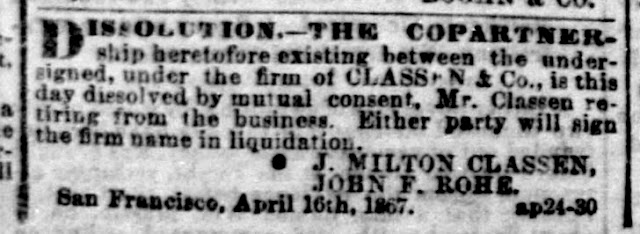

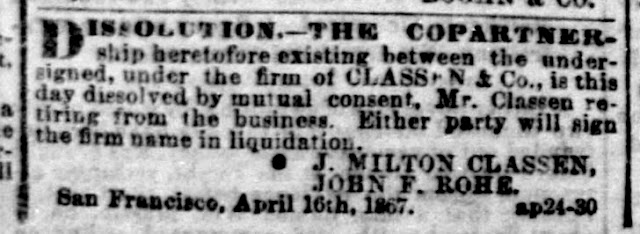

The dissolution notice of the partnership of the Pacific

Soda Works. Rohe became the sole owner but closed the business after a few

years and then became a trustee of the newly formed Bay City Soda Water

Company, . . .a corporation.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment